In case it should meet some misfortune I am placing here the text of a long essay in a history section of a Moscow paper. I am placing it here because it is an important story from an important perspective, one which we are denied in most western reporting.

This is for the same reason that I placed in this blog some weeks ago the text of a Russian essay in the same newspaper on Russia's difficulties in securing air superiority over Ukraine.

We are broadly aware that the present war in Ukraine began in 2014. We lack knowledge of the history leading from perestroika in the USSR though the independence processes up to the critical events at the end of 2013 and beginning of 2014.

The headline of the article is

How "Russian Spring" was born in Ukraine (1989 - 2014)

What follows is a google translation from Russian. The original is here:

https://history.vz.ru/kak_rozhdalas_russkaja_vesna_na_ukraine_(1989_-_2014)/5.html

The newspaper is here: https://vz.ru/

The processes culminating in Ukraine after the collapse of the USSR were the events of the winter-spring of 2014 - the reunification of Crimea with Russia and the uprising of the population of Donbass and the South-East of Ukraine against those who came to power in Kyiv as a result of the coup. This phenomenon was called the "Russian Spring" - a movement of Russian people who ended up in Ukraine after the collapse of the USSR and defended their civil rights and their identity.

Where did the Russians go

To understand the position of Russians in Ukraine, it is significant to compare the data of two population censuses conducted with a difference of 12 years - in 1989 and 2001. Since then, no censuses have been conducted by the Ukrainian authorities. One can only more or less reasonably extrapolate the tendencies of the first decade of Ukrainian independence to subsequent years.

According to the 1989 census , Russians made up 22.1% of the population of the Ukrainian SSR. In 2001, their share was already 17.3%. According to census data, Russians constituted the second largest ethnic group both in the entire Ukrainian SSR and in the absolute majority of its regions (the exceptions were Crimean, where ethnic Russians made up the majority of the population - 65.6%, and Transcarpathian and Chernivtsi regions, where Russians were the fourth by number).

The Russians are extremely unevenly settled on the territory of Ukraine. In the regions of Western, Northern and Right-bank Ukraine, the share of Russians ranged from 4% (Ivano-Frankivsk) to 8.7% (Kyiv). On the periphery of this macro-region there were regions in which the 1989 census recorded from 10% to 13% of Russians (Poltava, Kirovograd and Sumy). In eight regions, located in a single array in the south-east of the country, the share of Russians significantly exceeded the above figures: from 19.4% in Mykolaiv to 44.8% in Lugansk.

When compared with these data, the results of the 2001 census result in the following picture.

Within the first macro-region, where Russians made up up to 10% of the population, in most regions their share was almost halved. At the same time, in the South and East, the decline in the share of the Russian population did not have such a catastrophic scale and amounted to less than a third of the previous number. And if in the period from 1989 to 2001 Ukraine lost a total of about 1.7% of the population, then the number of the titular nation increased by 0.3%. At the same time, the number of Russians decreased by a total of just over a quarter (26.6%).

At the same time, the demographic hole that Ukraine fell into in the early 1990s also turned out to be quite selective. Western Ukrainian regions, in which no more than 2.6% of Russians remained, either increased the total population by 0.6–0.7% (Transcarpathian, Rivne), or if they lost their population, then very slightly - no more than 2.2% (Ternopil region, where 1.2% of Russians remained). At the same time, the Luhansk region, which in terms of the number of Russian population immediately followed the Crimea, lost more than 11% of the population.

Behind the dry numbers of demographic statistics, a disappointing picture of Ukraine's gaining national sovereignty emerges. The direct and obvious beneficiaries of independence were, first of all, the inhabitants of the western regions of Ukraine, who showed maximum political activity at the turn of the 80s and 90s of the last century.

Since no more censuses have been conducted in Ukraine since 2001, attempts were made to estimate the number of those who identify themselves as Russians using sociological methods. In particular, according to the Rating research group, from 2008 to 2014, about 15% of Ukrainian citizens considered themselves Russians. In 2014, this number decreased to 11%, including due to the loss of Crimea and the most densely populated part of Donbass by Ukraine.

At the beginning of May 2022, only 5% of respondents identified themselves as Russian. At the same time, sociological survey data is less accurate than population census data. Especially in crisis and conflict situations, when the respondent may deliberately distort his own point of view for security purposes or adjusting to a socially approved model of behavior. Also, the sharp decline in the share of the Russian population was affected by the loss by Ukraine in 2022 of a number of regions (parts of the Zaporozhye, Kharkiv, Kherson regions).

Imagine a portrait of two typical Ukrainians who lived in the Ivano-Frankivsk and Lugansk regions of Ukraine. They will speak different languages - Ukrainian in the first case and Russian in the second. Belong (at least formally) to different confessions - Greek Catholicism and Orthodoxy. The surname of a Ukrainian from Ivano-Frankivsk region will end in -chuk, and his children will be called Nazar and Solomiya. A Ukrainian from the Luhansk region will have a surname ending in -ko, and he will name his children Artem and Maria. The first one may well have relatives in Canada or Argentina, the second one will certainly have them in Russia.

The described image of a resident of the Lugansk region, by most signs, will be indistinguishable from a Russian from Rostov-on-Don or Voronezh. What makes him a Ukrainian is solely the state policy to create an imaginary national community. Remove this policy and there will soon be no trace left of Ukrainian identity.

Autonomous decay

A characteristic element of the disintegration of the USSR was the struggle of the regions for autonomous status. The autonomies raised the question of maintaining unity with Moscow in the event that their national republics declared independence. The idea of making the autonomous republics subjects of a new union treaty was actively discussed at the Novo-Ogaryovo talks as part of an attempt to preserve the USSR.

So, in 1989, the South Ossetian Autonomous Region proclaimed itself an Autonomous Republic within Georgia, which did not recognize this decision. And already in 1990, the South Ossetian Soviet Democratic Republic was proclaimed as part of the USSR. In response to this, the Supreme Soviet of the Georgian SSR completely eliminated the autonomous status of the region. Already in January 1991, hostilities broke out on this basis.

In September 1991, in response to the declaration of independence of Azerbaijan, the regional council of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region proclaimed a republic within the USSR. Already in the fall, a war began between the armed formations of Karabakh and Azerbaijan.

Somewhat differently than in Transcaucasia, where a system of autonomous republics and regions existed as part of the national union republics, the conflict proceeded in the Moldavian SSR with its unitary structure. In 1989, with the active participation of the Union of Writers of the Moldavian SSR and the People's Front that took shape on its basis, a law on the state language was adopted. In response, representatives of the Chisinau Intermovement, as well as local councils of Tiraspol and other settlements on the left bank of the Dniester, demanded that the Russian language be given the status of a second state language. After this demand was ignored, the largest enterprises of Transnistria, the most industrialized region of the MSSR, went on strike. When it did not bring success, the question of creating an autonomous republic was raised.

At the same time, if in Chisinau the nationalist forces demanded the unification of Moldova with Romania, then in Tiraspol they appealed to the autonomous republic that existed in the region in the 1920s-1930s as part of the Ukrainian SSR. In addition, there were deeper historical arguments. At the Congress of Deputies of Pridnestrovie on September 2, 1990, the "Political and Legal Justification for the Creation of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic" was adopted. In this document, for the first time in a political context, the word "Novorossiya" was used. The authors noted that the self-determination of the republic is based on “the formation of a certain ethnic group that inhabits today the south-west of the country (that is, the Soviet Union - ed.) and consists of descendants of immigrants from Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Poland, Germany, Greece and other countries . In practice, this ethnic group was formed by the time of the formation of Novorossia at the end of the 18th century as part of the Russian state.

A referendum on the proclamation of the republic was held in Rybnitsa in December 1990, in Tiraspol in January 1991, and then throughout the year local referendums were held in other settlements of Transnistria. An Autonomous Republic within the USSR and a special economic zone on the territory of the left-bank regions of the MSSR were proclaimed. Ultimately, already in the autumn of 1991, the conflict with Chisinau turned into an armed confrontation.

In Ukraine, as in Moldova, the starting point for separation from the USSR was the law on languages adopted at the end of 1989 by the Supreme Council of the Republic , in which Ukrainian was declared the only state language. The adoption of this law is considered the first practical step towards Ukraine's independence. The next was the proclamation of the Declaration of State Sovereignty of July 16, 1990, a little over a month after a similar document was adopted by the Congress of People's Deputies of the RSFSR. The failure of the "August coup" in 1991 in Moscow opened a direct path for Kyiv to an independence referendum.

Donbass: the struggle for autonomy and the preservation of the Union

In 1990 (that is, a year before the collapse of the USSR), an article appeared in the press organ of the Lugansk Komsomol - the Molodogvardeets newspaper - under the heading "It's impossible for us!" The article describes hypothetical scenarios for the separation of Donbass from Ukraine and its consequences.

The author, a local publicist, writer and political scientist Sergei Chebanenko, argued that whatever government is in Kyiv, communist or democratic, it will never voluntarily give up Donbass, and therefore the region’s secession from Ukraine cannot be formalized by legitimate procedures. This means that for such a branch, only the revolutionary path of mass popular protests is possible, which will provoke Kyiv to use armed force. If the separation of Donbass is supported by Russia, then this will lead to a war between the republics. On the other hand, according to the author, “Russian-speaking Nikolaev and Sevastopol” can follow the path of Donbass.

This publication was a response to the emergence in the Lugansk region of the People's Movement of Lugansk Region (NDL), whose leader, university lecturer Valery Cheker, demanded that the Kyiv authorities sign a new union treaty and grant Donbass "a new economic, political and social status" within its framework. According to Checker, the NDL “stands for autonomy within Ukraine, of course, if the republic signs a union treaty. And if this does not happen, then we can only talk about the transition to the jurisdiction of the RSFSR.

On the basis of the NDL, the Democratic Donbass movement was created, which appealed to the experience of the Galicians - by this time, an association of deputies of all levels of the three Western Ukrainian regions had been organized, called the Galician Assembly. The Assembly, headed by the leader of the nationalist People's Rukh of Ukraine, dissident Vyacheslav Chernovol, threatened Kyiv with secession if the leadership of Soviet Ukraine signed a new union treaty.

In turn, the activists of the Democratic Donbass proposed to convene the Donetsk Assembly, proclaim the Republic of Little Russia with its center in Luhansk, and linked its preservation as part of Ukraine with the preservation of Ukraine as part of the Union. It is indicative that the historical term “Novorossiya”, which is more correct for Donbass, was so firmly forgotten during the Soviet period that Russian activists of the Luhansk region during perestroika, unlike their Pridnestrovian associates, may have been simply unknown (in 2016, under the influence of Russian writer Zakhar Prilepin about the creation of Little Russia was declared by the head of the Donetsk People's Republic Alexander Zakharchenko). However, from the radical idea of the "Republic of Little Russia", as well as from the creation of their own power units to protect it,

The most famous Russian public association of those years was the Donetsk Intermovement of Donbass. In January 1989, the founding congress of the International Workers' Front of the Latvian SSR, or Interfront for short, was held in Riga. One of its leaders was the People's Deputy of the USSR, military engineer, Colonel Viktor Alksnis. Soon similar interfronts arose in other Baltic republics, in Moldova and some other regions of the Soviet Union. In this row is the International Front of Donbass.

The main doctrinal principle of the organization at that moment was the preservation of the Soviet Union. At the same time, the activists of the Intermovement demanded the autonomy of Donbass within Ukraine and the general federal-land reorganization of the unitary national republic. The Intermovement also fought for the official status of the Russian language, guaranteeing its equality with Ukrainian, and opposed Ukrainian nationalism.

The creator and ideologist of the Intermovement of Donbass was Dmitry Kornilov. The organization developed and put into use a black-blue-red tricolor, which years later will turn into the flag of the Donetsk People's Republic. A special role in the activities of the Intermovement was played by the popularization of the historical memory of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic during the Civil War. At the same time, the Intermovement was not a form of communist revenge in the republics that wanted to break away, but one of the directions of the democratic movement that originated at the decline of the USSR and opposed the party nomenklatura, which was turning into the national elites of the new independent states before our eyes.

The idea of a referendum on the proclamation of an autonomous republic in the Donbass was actively discussed in the regional press, at rallies and meetings of public organizations. The local authorities could not ignore this issue either. Back in September 1990, the Donetsk City Council prepared a draft Declaration on the economic sovereignty of Donetsk and the status of the city within the Ukrainian SSR. A year later, in October 1991, the issue of the status of the region was submitted to the session of the Donetsk Regional Council, which adopted an appeal to the Supreme Council of Ukraine with a proposal to introduce a federal-land structure into the draft Constitution of Ukraine, and to adopt the Constitution itself at a national referendum.

The continuation of this official initiative was a meeting of people's deputies of all levels of the South and East of Ukraine, held in Donetsk on October 26, 1991. An appeal was adopted to the Supreme Council of Ukraine with a proposal “Introduce the provision on the federal land structure of Ukraine into the concept and into the draft Constitution of Ukraine; during November 1991 to discuss the draft of the new Constitution of Ukraine and submit it for public discussion.

However, in the end, the idea of the region's autonomy was never realized. The failure of the State Committee for the State of Emergency in 1991 neutralized those who could count on the use of force to preserve the unity of the Union. An attempt to rely on the KGB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the army proved fruitless in the capital, and the over-centralized Soviet system did not allow for such an initiative on the ground. But the main thing is that after Yeltsin's victory, the issue of a new union treaty, to which the autonomists hoped to become subjects, was already removed from the agenda and was no longer returned to it. At the same time, the real political force of Donbass - the strike movement of miners - was focused on socio-economic, rather than political problems, and it seemed to many then that it would be easier for independent Ukraine to solve them.

Crimea. With the Republic, but without the Union

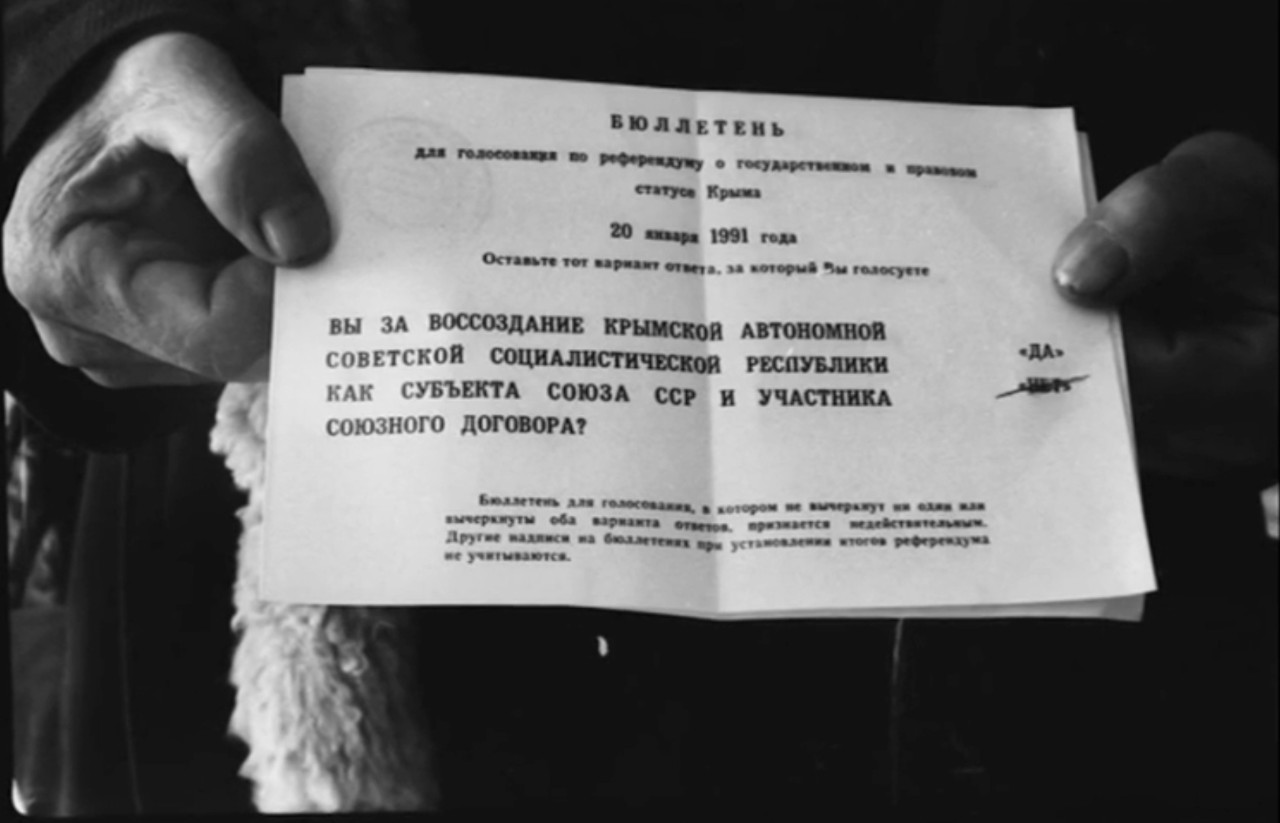

While Donetsk and Lugansk failed to achieve autonomous status in 1991, Crimea proved to be more successful along the way. In January 1991, an important step was taken towards formalizing the political self-determination of Russians in Crimea - a referendum on "the re-establishment of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic as a subject of the USSR and a participant in the Union Treaty."

Back in 1989, in connection with the rehabilitation of the Crimean Tatar people, the issue of restoring the Crimean ASSR was raised at the central level. The process of the return of the Crimean Tatars to the peninsula took place in a tense, conflict situation, which is typical in general for interethnic relations at the end of the Soviet era.

In the autumn of 1989, the People's Front appeared in Crimea. Such associations appeared throughout the Union, initially declaring support for Gorbachev's perestroika. They were supposed to support the democratic initiatives of the Soviet leader on the ground, helping to overcome the resistance of the conservative central apparatus. However, within the framework of these associations, opposition to the CPSU as such and its monopoly on power very quickly began to take shape.

In the national republics, primarily the Baltics, Moldova, Georgia, the popular fronts very quickly became a stronghold of nationalism and separatism. Ukraine was no exception, where the association was called Narodny Rukh. The initiators of the creation of the organization were Ukrainian Soviet writers (Ivan Drach, Dmytro Pavlichko, Boris Oliynyk), who took an active part in the development of a new language law.

In Crimea, local democratic forces chose to distance themselves from Ukrainian nationalism and created their own, regional “front”. In other national republics, this was not observed, but it was typical for the RSFSR, where there was no own united Popular Front, but the Moscow, Leningrad, Kuibyshev, Chelyabinsk, Don, etc. "popular fronts" were actively operating.

It was the Crimean People's Front that raised the idea of reviving the status of an autonomous republic to its shield. Voices began to be heard in favor of the return of Crimea to Russia, since Crimea had the status of an autonomous republic within the RSFSR, and the Ukrainian SSR was a unitary entity. Consequently, the supporters of this idea believed that the revival of the status of autonomy also implies a change of jurisdiction - from Ukrainian back to Russian.

The idea of Crimea gaining a higher republican status and maintaining its unity with the entire large country also had a socio-economic dimension. The way out of the crisis in the Crimea was seen as the transformation of the peninsula exclusively into a resort region. And this could give the expected effect only on the scale of the “all-Union health resort”.

Under the pressure of three political factors - Kyiv's choice of a course towards building an independent Ukrainian national state, the growth of interethnic tension in Crimea itself and competition from the "democrats" - the party elite of the Crimean region, which had previously taken a wait-and-see position, switched to republican positions.

The Crimean referendum in January 1991 was the first plebiscite in the history of the USSR. More than 81% of voters took part in the voting, more than 93% of whom answered “yes” to the question submitted to the referendum: “Are you in favor of recreating the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic as a subject of the USSR and a participant in the Union Treaty?” The legitimacy of these results was not disputed by either Kyiv or Moscow.

However, the results of the referendum were not fully implemented. Crimea restored the status of an autonomous republic, but it was not destined to become a subject of the new Union Treaty. The new treaty was never signed. Instead, the leaders of the three union republics (the RSFSR - Boris Yeltsin, the Ukrainian SSR - Leonid Kravchuk and the Byelorussian SSR - Stanislav Shushkevich) on December 8, 1991 in Belovezhskaya Pushcha signed an agreement on the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), in the very first lines of which they stated that " The Union of the SSR ... ceases to exist. At the same time, Crimea was actually abandoned by Yeltsin, who was in a hurry to gain full power in the RSFSR, and thus left as part of Ukraine. And in December 1991, a referendum on the independence of Ukraine and the election of its president took place.

1991. Choice in the process of disintegration

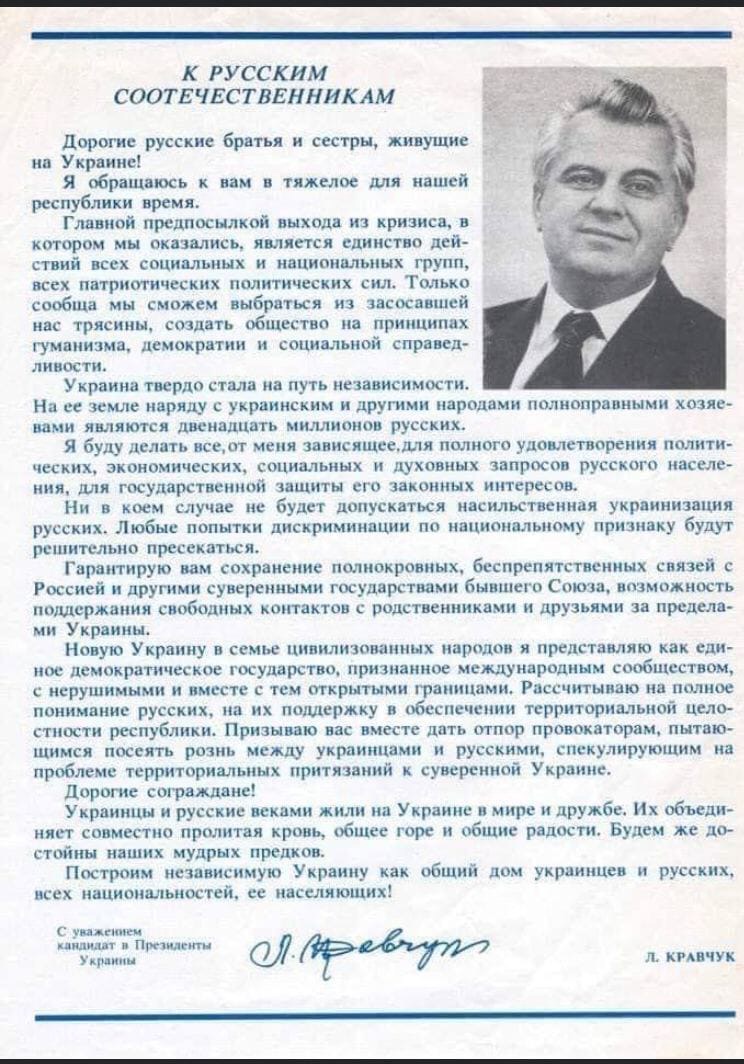

The place the Russian question occupied in Ukrainian politics is shown by the election leaflet of Leonid Kravchuk, then a presidential candidate and chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, whose signature was already under the act of declaring independence and under the Belovezhskaya agreements. In the recent past, a member of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the head of the ideological department of the Communist Party of Ukraine issued an open appeal "To Russian compatriots." No other national group has received such special attention.

Addressing “brothers and sisters” in a Stalinist way, Kravchuk called the Russians living in the republic “full owners” of the Ukrainian land, guaranteed that he would not allow “forced Ukrainization”, promised to maintain “full-blooded ties with Russia”, called for building an independent Ukraine as a state of “Ukrainians” and Russians, of all nationalities inhabiting it.

For the Russians, this appeal recognized the existence of certain special “political, economic, social and spiritual needs”, as well as “legitimate interests” that needed state protection. The presidential candidate expressed hope for support from the Russians "in ensuring the territorial integrity of the republic" and mentioned some provocateurs who sow interethnic discord and speculate "on the problem of territorial claims to sovereign Ukraine."

The assurances that sounded from the lips of the father of Ukrainian independence at its dawn coincided with the political programs of parties and movements that were commonly called pro-Russian. And the rhetoric chosen by Kyiv was designed to prevent internal separatism and the claims of neighbors, primarily Russia.

In 1991, Kravchuk confidently won the presidential elections in independent Ukraine. Residents of the Ukrainian SSR, disoriented by the grandiose processes of the fall of the Communist Party and the collapse of the Soviet Union, then twice during the year supported the opposite ideas in referendums. First, a majority of votes were in favor of the preservation of the USSR, and then - for the independence of Ukraine. The second vote, as well as the election of yesterday's top functionary of the CPSU to the post of head of state, for ordinary citizens was an attempt to protect themselves from the consequences of a large-scale geopolitical catastrophe.

It took only one round for Leonid Kravchuk to win. He ensured such a result by winning in all regions of Ukraine, with the exception of three Galician regions - Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil, where the dissident, leader of the Narodny Rukh, Ukrainian nationalist Vyacheslav Chernovol won. In two Volyn regions - Volyn proper and Rivne, the gap in favor of Kravchuk was minimal. Third after Kravchuk and Chornovol was another Ukrainian nationalist and former dissident, a native of Chernihiv region Levko Lukyanenko.

The fourth place in the presidential elections was taken by Vladimir Grinev from Kharkiv. Grinev was the vice-speaker of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. On August 24, 1991, he refused to support the Act on the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine and opposed the ban on the Communist Party. Judging by the results obtained, it was Grinev who was the "candidate from the South-East" in those elections.

The highest percentage was received by Grinev in the Donetsk region (11%) and almost the same in the Kharkiv region (10.9%). Slightly less - in the Crimea (9.4%) and Odessa (8.4%). For comparison: 11% was received by the winner of the elections Kravchuk in the Lviv region. Above the average for Ukraine (4.1%), Grinev also managed to get in Lugansk (6.7%) and Mykolaiv (5.6%) regions, a close result (3.9%) - in Zaporozhye.

The political contours and configuration of the Russian part of Ukraine were guessed already at the dawn of its independence, concentrating primarily in the cities, although it lost in terms of monolithic voting to the Western part of Ukraine.

In the extraordinary presidential elections in Ukraine in 1994, Grinev supported Leonid Kuchma, with whom he had collaborated since the early 1990s. As a confidant of the candidate, he made campaign trips to the cities of Novorossia, where he showed a good result in the 1991 elections. In many respects, it was this that contributed to the approval of Kuchma as a “pro-Russian” candidate, which made it possible to win the elections.

Grinev, a supporter of the federalization of Ukraine, received the post of presidential adviser on regional policy. However, Kuchma soon distanced himself from pro-Russian advances to his voters, and the liberal market reforms that Grinev had always advocated fell out of favor in both Ukraine and Russia. They hit hardest of all just on engineers, teachers, researchers, who made up the electoral base of such politicians as Vladimir Grinev. But it was they who predetermined the renaissance of the left forces in the second half of the 1990s.

After the collapse. 1992–1994

After the formal liquidation of the USSR, the severe socio-economic crisis, which became one of the reasons for the collapse of the Union, did not disappear anywhere. Against this background, a new struggle for power is unfolding in the former Soviet republics. In 1992, in the immediate vicinity of the borders of the Ukrainian SSR, the conflict between Moldova and Transnistria entered the armed phase. In Russia, the conflict between President Yeltsin and the Supreme Soviet ended in 1993 with street fighting in Moscow and the shooting down of the building of the Russian parliament.

In Ukraine, as in other republics, the basis of the political crisis was the confrontation between the president and parliament against the backdrop of acute internal socio-economic problems. As in 1991, the national question reminded itself of itself.

In late February - early March 1992, Novorossia first encountered Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary formations. The "train of friendship" of the UNA-UNSO militants (an organization banned in the Russian Federation) first visited Odessa, where the nationalists staged a pogrom in the city prosecutor's office, and then reached Sevastopol through Nikolaev, Kherson and Simferopol.

The route of the train is indicative. The leader of the militants, Dmitry Korchinsky, openly stated that the show of force was addressed to the separatists entrenched in the southern region. The nationalists did not meet any organized resistance, but their visit activated the Russian movement.

Odessa remembers Novorossiya, and Crimea elects a president

In 1993, the Odessa City Council for the first time among the regional centers of Ukraine (the first regional center to make a similar decision was Mariupol on November 5, 1991) decided to use the Russian language along with Ukrainian in its work. The initiator was a young politician, the leader of the movement Civil Forum "Odessa" Alexei Kostusev (later one of the leaders of the "Union" party, then a member of the political council of the "Party of Regions" and the mayor of Odessa in 2010-2013).

At that time, preparations were underway in Odessa for the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the founding of the city, which provoked a heated political discussion. Thus, in 1992, the Obozreniye newspaper published an article with an eloquent headline: “We are Novorossiy”, the author of which stated, in particular, the following:

“Having emerged from many years of oblivion, the word “Novorossiya” is now surprisingly misunderstood by those who do not know or have forgotten their history. Political adventurers, who dreamed of recreating on the ruins of one sixth of the land of a medieval dumpling-sharovan utopia, with obscene hoots and “shouting”, are trying to distract the old-timers of the Black Sea region from the revival of their self-awareness and self-understanding ...

We consider it anti-historical and blasphemous to impose on our land a mono-national Ukrainian culture in its worst tribal expression: we reject the trend of turning Novorossia into a “Step Ukraine” invented by the ideologists of nationalism ...

Our land has become the country of destiny for many talented people who did not want to evaluate their neighbor on a national basis. And by the will of History and Fate, Odessa, founded according to the decree of Catherine the Great in 1794, became the pearl of New Russia.

The intellectual response of Ukrainian nationalists was the assertion that the 200th anniversary of the city is a “myth” that feeds the independence of the “fictitious Novorossiya” and creates a “theoretical basis for anti-Ukrainian resistance on the Black Sea coast.” It was in this context that the theory about the 600-year age of Odessa appeared, formulated for the first time in the book of the same name by amateur historian Alexander Boldyrev.

But a much more serious "resistance" took place in the Crimea. Here, literally on the eve of the visit of Ukrainian nationalists, the Republican Movement of Crimea was transformed into a party of the same name, led by Yuriy Meshkov. Meshkov was a lawyer, and began his social activities as the leader of the Crimean branch of the all-Union "Memorial" - a public organization engaged in perpetuating the memory of the victims of Soviet political repression. In 1991, Meshkov openly spoke out against the State Emergency Committee. And it was he who uncompromisingly became the head of the struggle for the reunification of Crimea with Russia.

Activists of the Russian movement have started preparing a new referendum on the self-determination of Crimea. In October 1993, the Supreme Council of the peninsula introduced the post of president, and in January 1994, Meshkov was elected to this position as the leader of the electoral bloc with the eloquent name "Russia". In the second round of presidential elections in the autonomy, Meshkov received 72% of the vote. It is significant that the leader of the Crimean Communists Leonid Grach took 4th place, gaining 13% in the first round. In the spring of 1994, the Rossiya bloc won the elections to the Supreme Council of Crimea, whose speaker was one of the leaders of the Russian Community of Crimea and the Republican Party, Sergei Tsekov (currently a senator from Crimea in the Federation Council of Russia).

However, at that moment there was no necessary unity in the Crimean elites, and the process of gaining full sovereignty by the republic was drowned in political battles.

Donbass holds a referendum

In 1992, the “Civil Congress” party was created in Donetsk, co-chaired by Donetsk teacher of philosophy Alexander Bazilyuk, Kharkov archaeologist and current deputy of the Verkhovna Rada Valery Meshcheryakov and Crimean writer, founder of the “Russian Community of Crimea” Vladimir Terekhov. All three came from the democratic movement of the perestroika era, and after the collapse of the Union, they opposed the former party nomenklatura, which repainted as Ukrainian nationalists. The "Civil Congress" advocated the equality of the Russian language and the federal reorganization of Ukraine. At the stage of formation, the future Prime Minister of Ukraine Mykola Azarov was in its ranks.

In addition to democratic forces, the left, primarily the communists, claimed the pro-Russian vector in Ukrainian politics. By a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR on August 30, 1991, following the failure of the State Emergency Committee and the declaration of independence of Ukraine, the Communist Party was banned. However, already in May 1993, the Presidium of the Supreme Court allowed the creation of a new communist party in the country, which was done at the first congress of the Communist Party of Ukraine, in June of the same year in Donetsk. The party was led by Petr Simonenko, former second secretary of the Donetsk regional committee.

Since December 1993, Donbass has been gripped by an indefinite strike of miners. Yielding to the demands of the strikers, the Verkhovna Rada announced a referendum on confidence in the president and parliament, which was to be held on March 20. However, at the last moment, the Rada and President Kravchuk agreed to early elections.

Parliamentary elections were to be held on 27 March. In these circumstances, the Donetsk and Luhansk regional councils decided to hold their own referendum in parallel, which should have included questions about the federal structure of Ukraine (only in Donetsk), the status of the Russian language and integration in the post-Soviet space. Thus, for the first time, the entire key block of problems related to the political Russian movement in Ukraine was formulated. The Intermovement of Donbass took an active part in the preparation of the referenda. With a turnout of over 70%, the vast majority of citizens supported the initiatives put to the referendum.

Elections–1994

Following the results of the 1994 parliamentary elections, which were held on a completely majoritarian basis, the majority of seats in parliament were won by non-partisan self-nominated candidates. But among the parties, it was the revived KPU that brought the largest number of deputies to the Rada, having issued a pronounced “red belt”. So, in the Luhansk region, out of 23 districts, 14 turned out to be communists, in Donetsk - 24 out of 48, in Kherson - 5 out of 10, Nikolaev - 5 out of 11, in Crimea (with Sevastopol) - 10 out of 23, in Zaporozhye: out of 18 - 7. This list does not include three regions with key cities - Kharkiv (6 out of 25), Odessa (6 out of 23) and Dnepropetrovsk (1 out of 34). For comparison, the Communists got more favorable results in several regions of Northern and Central Ukraine. Thus, it is seen that a unified political agenda for all regions of historical Novorossiya was just beginning to take shape. From the pro-Russian party "Civil Congress" two majoritarian deputies from Kharkiv and Donetsk region entered the parliament.

The tendencies that manifested themselves in the 1994 parliamentary elections were fully manifested in the presidential elections, the first round of which took place three months later. In the first round, Leonid Kuchma received 83% of the vote in Crimea, 54% in Donetsk and Lugansk regions. And for his competitor Leonid Kravchuk in the first round, 91% of active voters in Ternopil, 90% in Lviv and 89% in Ivano-Frankivsk regions voted. He received slightly less support in Volhynia. The second round showed even more vividly the political split of Ukraine.

Kuchma's Ukraine becomes Non-Russia

The electoral dynamics showed that Kuchma was voted for primarily as a "pro-Russian" candidate. But it was during his presidency that an intense wave of Ukrainization occurred, which was carried out with the help of administrative measures - presidential decrees, Cabinet resolutions, various by-laws and court decisions that limited the spread of the Russian language.

Crimea, which provided Kuchma with unprecedented support, already in 1995 was deprived of sovereignty. Taking advantage of the internal split in the political elites of the peninsula, Kyiv liquidated the constitution of the Republic of Crimea. Yuri Meshkov was forced to emigrate to Russia. In July 1996, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine sent a document to the government of Crimea with the title: "On measures aimed at ideologically ensuring the status of Crimea as an integral part of Ukraine."

Having dealt with the Crimean autonomy, Kuchma launched an offensive in the humanitarian sphere. In the fall of 1996, the ORT channel, as the First Channel of Russian Television was called at that time, stopped broadcasting in Ukraine. Instead, Inter appeared on the air, the very name of which hinted at the international character of the channel. Indeed, ORT acted as a minority shareholder of the new television company. Russian entertainment content, which had no competitors on Ukrainian television for a long time, both on television and in the advertising market, formed the basis of Inter's broadcasting. But socio-political and information programs were now made in Kyiv. Ultimately, in 2002, almost all the programs of the Russian channel disappeared from the Ukrainian air.

Kuchma's Ukrainization reached its peak when Viktor Yushchenko (2001-2002) became prime minister, in whose government humanitarian posts were occupied by Ukrainian nationalists. One of the reasons for this reversal was the struggle around the draft Constitution of Ukraine, adopted in 1996. Kuchma managed to achieve maximum powers for himself, which allowed him to virtually single-handedly control the fate of the gigantic economic assets that Ukraine inherited from the USSR. In exchange for political support for his project, the president gave Ukrainian nationalists the ideological and humanitarian spheres. The Constitution stipulated the state status only for the Ukrainian language and a unitary political structure.

This is how the political model of “Kuchmism” was formed, when the oligarchic elites of the East of Ukraine gained control over the economy, and the political elites of the West - over ideology. At the same time, the system was overloaded with internal conflicts, in which the president, who had the widest powers, acted as the supreme arbiter. The ideological narrative of “Kuchmism” was a book published on behalf of the president with the telling title “Ukraine is not Russia”.

Left turn

The Russian movement of the 1990s in Ukraine grew as an integral part of the general democratic movement of the times of perestroika in the late USSR and, by the end of the decade, completely lost its social support. The urban intelligentsia of the South and East was demoralized by the results of market reforms. The “Civil Congress”, which represented this electorate, changed its name to the “Slavic Party” and included in its membership the assets of the abolished Republican Party of Crimea, headed by Sergei Tsekov. However, all this did not help the party to break into the front row of the Ukrainian politicians, as well as the similar “Russian Bloc” of Alexander Svistunov. These parties systematically promoted their candidates for local councils only in Crimea and sporadically in other regions of the South-East, and later their remnants were blocked with the "Party of Regions".

The industrial proletariat of these regions suffered no less from deindustrialization. As a result, left-wing parties, for which the national question played an optional role in those years, became a real counterbalance to the policy of official Kyiv.

Voters who felt the “dashing 90s” on themselves preferred to support the revived Communist Party of Ukraine, headed by Simonenko from Donetsk, or the more radical Progressive Socialist Party of Ukraine from Kiev, Natalia Vitrenko, because, in addition to purely humanitarian issues, their main strong point was social issues. Thanks to the influence of the left, many liberal economic reforms carried out in the Russian Federation in the 1990s and early 2000s (land market, monetization of benefits, etc.) were not implemented in Ukraine, despite the position of the government and Western creditors.

The Communists became victors in the 1998 elections to the Verkhovna Rada and were actively preparing for the presidential campaign. Natalya Vitrenko, who split off the pro-Russian wing from the more moderate and quite popular in the rural Ukrainian province of the Socialist Party of Alexander Moroz, was accused by opponents of splitting and discrediting the left forces in the interests of the Kuchma administration. However, it was this party that became the center of attraction for all the activists of the “red-brown” (to use the definition of supporters of the Supreme Soviet of Russia in conflict with Yeltsin in 1993) political spectrum. Because of this, she actively interacted with some Russian and even Orthodox political groups for whom an alliance with more orthodox communists was not possible.

However, the Russian movement of the 1990s still managed to achieve certain results. Under his pressure in 1999, Ukraine was forced to ratify the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

One of the key initiators of its adoption was the Kharkiv deputy Vladimir Alekseev. In the Verkhovna Rada, he and two hundred other deputies formed an inter-factional association to protect the Russian language. The background for this decision was the struggle waged by the local representative bodies. Back in 1996, the Kharkiv city council announced the free use of the Russian language in local government. This was followed by similar decisions of the Donetsk Regional Council and the Supreme Council of Crimea (1997).

However, these decisions were canceled by the prosecutor's office and the courts, and Kharkiv residents began to look for a legal basis in the struggle for their native language. Already after the adoption of the Charter in April 2001, the Kharkiv city council confirmed that its decision on the free use of the Russian language along with Ukrainian remained in force despite the fact that the authorities threatened to dissolve it. Moreover, a consultative referendum was announced, which was scheduled for 2002 in parallel with the next elections to the Verkhovna Rada. 87% of active voters supported the official status of the Russian language.

In addition to Odessa, Kharkov, regional centers and large cities of Donbass (Mariupol, Enakievo, Gorlovka, Alchevsk, Lisichansk), the official status of the Russian language was adopted in Nikolaev, Kherson and Zaporozhye. In 2002, the regional councils of Dnepropetrovsk, Luhansk and the Supreme Council of Crimea appealed to the Verkhovna Rada with a demand to hold a referendum on the status of the Russian language, but it was ignored. In all local councils, the initiators of such decisions were activists from various Russian and pro-Russian parties and public organizations.

It must be admitted that at that time Ukrainization was still of a rather mild and gradual nature, and the population concerned about the banal survival against the backdrop of the crisis did not perceive it as problem No. 1. Moreover, this movement could not even purely symbolically rely on the liberal Russia of Boris Yeltsin, which was going through a series of political and economic crises. At the same time, the Russian movement in Ukraine, with the exception of Crimea, tried to play the role of an all-Ukrainian force, which clearly exceeded its real capabilities, instead of concentrating on work in the base regions.

Against this background, President Kuchma in 1999 managed to be re-elected for a second term. His potential rival, Rukh leader Vyacheslav Chernovol, died in a car accident six months before the elections. Now Kuchma was going to the polls as a candidate, first of all, from Western Ukraine, having received over 90% of the votes in these areas in the second round. At the same time, Kuchma managed to achieve a final victory in such key regions as Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk, and even the native Donetsk region for his main opponent, the communist Simonenko.

It seemed that the territorial division of Ukraine had been overcome, and the Russian question was no longer a political factor. On the other hand, since the beginning of the 2000s, the recovery growth of the economy began in Ukraine, the socio-economic situation has stabilized. However, this was only the calm before the storm.

The Orange Revolution and the Blue and White Counter-Revolution

When, along with economic growth, the acuteness of the problem of physical survival was removed, for the majority of the population, questions of identity again came to the fore, aggravated not only by the policy of forced Ukrainization implemented by the Kuchma administration, but also by the changed foreign policy situation.

In 1993, when economic cataclysms, political crises and local wars shook the post-Soviet space, integration processes acquired a new quality to the west of it - the European Union was formed. A few years later, the former Central European countries of the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet republics of the Baltic states submit applications for joining the new association.In 1999, three of them (Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary) become members of the NATO military-political bloc.In 2004 seven more countries (Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria and Romania) join them. Most NATO recruits become members of the European Union in the same year.

In 2000, Vladimir Putin became president of Russia. He manages to stop the disintegration of the country, stabilize the socio-economic situation, strengthen Russia's position in the international arena. All this brings him extremely high popularity not only among Russian citizens, but also among his neighbors, including in Ukraine. Putin is launching new integration projects in the post-Soviet space - the SCO, the CSTO, the Customs and Eurasian Unions.

At the same time, in Yugoslavia, as a result of mass protests organized using special political technologies, President Slobodan Milosevic was removed from power. The Yugoslav protests are considered the first "color revolution" in Eastern Europe, followed by similar events in 2003 in Georgia, where Mikheil Saakashvili came to power.

All these factors overlapped in Ukraine at the turn of 2004-2005, when, as a result of another “color revolution” (the so-called Orange Revolution), Viktor Yushchenko, a supporter of neoliberal reforms, Euro-Atlantic integration and Ukrainian nationalism, became president. It was these three elements that determined the state policy of Kyiv during the years of his presidency.

Yushchenko's competitor was Viktor Yanukovych, the current Prime Minister of Ukraine at the start of the 2004 election campaign. Yanukovych was a native of Donbass, made a career there, and during the time of Leonid Kuchma became the head of the Donetsk regional administration. Behind him stood the "Donetsk clan", which intertwined representatives of the late Soviet nomenklatura (such as Yefim Zvyagilsky and Vladimir Rybak), and oligarchs who gained control of the largest industrial enterprises in the region (such as Rinat Akhmetov and Boris Kolesnikov).

The elections of 2004-2005 for the first time so clearly and unequivocally showed the political subjectivity of the South-East of Ukraine, from Kharkov to Odessa. Basically, these are the territories of the historical region, known since the end of the 18th century. under the name Novorossiya.

Political technologists of Yanukovych and his entourage realized that it was impossible to compete in the elections with Yushchenko, a candidate popular in the western and central regions of Ukraine, relying on a broad coalition of Ukrainian national-democratic and nationalist forces, supported by the West and a powerful parliamentary faction, remaining on the obscure political agenda of late Kuchmism. . It made no sense to compete with Yushchenko in Kuchma's role of a "soft" Ukrainizer, a supporter of European integration and a "strong business executive" (it was from these positions that the programmatic work "Ukraine is not Russia" was written) made no sense. For all these positions, the "orange" candidate looked more attractive - he was a greater patriot,

Yanukovych was forced to mobilize the electorate, borrowing the agenda of the Russian movement - the status of the Russian language, the federalization of Ukraine, integration with Russia, the rejection of Ukrainian nationalism, the glorification of the OUN-UPA, Euro-Atlantic integration.

After the second round of voting took place on November 21, a mass protest rally under the orange flags of Yushchenko's election campaign started on Independence Square in Kyiv. Skillfully using the technologies of non-violent resistance with the diplomatic support of Western countries, Yushchenko's team achieved the annulment of the election results. At the same time, by decision of the Lviv, Volyn, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk and Kyiv regional councils, it was Yushchenko who was declared the winner of the election race.

Local governments in those regions where Yanukovych received the most support took action in response. On November 26, the Luhansk Regional Council adopted a resolution "On strengthening the organizational structure of local authorities in the Lugansk region." It contained the following clause: “Submit for consideration by the congress of local governments and executive authorities of the South-Eastern Territories of Ukraine a proposal to organize a working group to create and form a tax, payment, banking, and financial system of the South-Eastern Territories.” This decision launched the process of creating an autonomous republic in the South-East, not subordinate to Kyiv, in the event that Yushchenko came to power there in an unconstitutional way. The next day, a decision similar to the Luhansk one was adopted by the Kharkiv Regional Council.

On the same day, in a resolution of a meeting of Yanukovych supporters in Odessa, the word Novorossiya was first used - this was the name of the region centered in Odessa, which would announce its separation from Ukraine if nationalist forces came to power in Kyiv as a result of a coup.

From Maidan to Maidan

Viktor Yanukovych and the elites of the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine that rallied around him turned out to be unprepared for the “color revolution” scenario imposed on them. They lost in the information field - both in traditional media and on the Internet. They lost on the street - they had nothing to oppose to a pre-prepared network of activists of non-profit organizations. Finally, they succumbed to pressure from the West.

Only the threat of losing the South-Eastern regions of Ukraine, voiced at the congress of deputies of all levels in Severodonetsk in November 2004, could stop the "triumphal march" of the revolutionaries.

The Ukrainian elites preferred a compromise. Contrary to the Constitution, the third round of elections was announced, in which Yanukovych was obviously defeated. Voting took place on December 26, 2004, and on January 10, 2005, Yushchenko was declared the winner. However, the constitutional reform carried out in December redistributed powers from the President to the Parliament. This mitigated the cost of defeat and guaranteed the Yanukovych team the preservation of political subjectivity. These guarantees turned out to be enough for the elites of the South-East, and they let the process of autonomization of the region come to a halt, refusing not only practical actions in this direction, but also the most radical rhetoric. As a result, even those criminal cases that were opened on charges of separatism against the leaders of the blue and white camp were closed.

Nevertheless, having suffered a painful defeat, a significant part of the nomenklatura of the Kuchma era tried to distance themselves from Yanukovych, moving into the camp of opponents, taking a wait-and-see attitude or completely withdrawing from business. Nobody believed in the political future of the Donetsk group leader.

However, the "Party of Regions" managed to regain its lost positions in power, while it began its revival, relying precisely on the Russian movement. The start of the election campaign of the "regionals" in the 2005 parliamentary elections was given on June 12, that is, on the Day of Russia in Simferopol, at an event organized by the Russian Community of Crimea. Yanukovych became an honorary member of this organization along with such figures as Yuri Luzhkov, Konstantin Zatulin and Alexander Dugin. In 2006, at the local elections in Crimea, the Regions chose to abandon their party brand for the only time, forming the “For Yanukovych” bloc with the Russian organizations of Crimea. And it gave a very successful result.

"Regionals" began to integrate other systemic pro-Russian forces of the South-East. However, according to the tradition of Ukrainian politics, the closer the applicant was to power, the further he became from Russian software installations.

The last major successes of the pro-Russian wing in the Party of Regions were the adoption of the so-called Kivalov-Kolesnichenko language law (written on the basis of the program for the preservation and development of the Russian language of the Odessa City Council), which granted the Russian language a full-fledged regional status, and the ratification of the so-called Kharkiv agreements with the Russian Federation on maintaining the base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol. Following this, Yanukovych turned the course 180 degrees and embarked on the path of European integration, which ultimately led him to the loss of power, flight to Rostov-on-Don, and Ukraine to civil war.

The establishment of the "Party of Regions" as the main pro-Russian force against the backdrop of the end of the economic crisis of the 1990s pressed the positions of the left forces. After the parliamentary coalition of 2006, the Socialist Party lost its electoral core in central Ukraine, and the CPU remained in the status of a junior partner of the Regions.

In 2005-2007, Natalia Vitrenko's Progressive Socialist Party of Ukraine (PSPU) became a point of attraction for those who rightly considered the Party of Regions to be too soft and inconsistent in defending Russian interests. During this period, there were the most resonant actions of direct action, in which the PSPU played an active role: disruption of NATO exercises in the Crimea in 2006 and 2007, counteraction to the UPA march on Khreshchatyk in Kyiv in 2007. In 1998, she managed to get her party into the Rada, receiving 4.4% of the vote. However, this was the greatest success of the Progressive Socialists. PSPU bore the generic problems of the Russian movement of the 1990s - the archaic methods of political struggle, leaderism, leading to internal conflicts and splits, the imprint of marginality.

Gradually, the niche of the radical pro-Russian force was occupied by younger political projects. In 2011, a landmark book by the Donetsk historian, director of the Ukrainian branch of the Institute of the CIS countries Vladimir Kornilov “Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic. A shattered dream." The book is dedicated to how, as a result of Lenin's national policy, Kharkiv and Donbass ended up as part of Ukraine. Modern Russian autonomists appealed to the historical experience of those years, while Ukrainian nationalists considered Kornilov's book a guide to separatism.

A few months earlier, activists of the parties "Russian Unity" - a deputy of the Supreme Council of Crimea Sergey Aksenov and "Rodina" - a deputy of the Odessa City Council Igor Markov, with the participation of a number of friendly public organizations, held an action unprecedented for the Russian movement - the celebration of May 9 in Lviv under the red flag of Victory . The reaction of local nationalists resulted in riots, and only the professionalism of the police made it possible to avoid bloodshed.

The pro-Russian forces began to stake on a new generation of the Russian movement - young, well-educated and ideologically motivated activists. It was these people who, in the ten years that have passed since the first Maidan, prepared the ground for the Russian Spring of 2014 with their activities. The Russian movement actively adopted methods that previously ensured victory in Ukraine for nationalist and Euro-Atlantic forces: network structures, its own media, working according to modern media standards, social networks, direct action, street activism, interaction with civil society, etc.

The February 2014 coup d'etat and the ensuing mass movement of those who did not accept the results of the Maidan drew a line under the history of the Russian movement in Ukraine. It was no longer possible to exist further as a full-fledged social force within the framework of the Ukrainian state. Legitimate democratic mechanisms for protecting their rights and interests have been exhausted. The authorities have formed a public consensus, according to which the Maidan is the greatest achievement of the Ukrainian people, and Russia is the aggressor country. Everyone who did not fit into this consensus was either marginalized, like the remnants of the Party of Regions, or physically eliminated, like the writer Oles Buzina.

The annexation of Crimea by Russia, unrecognized by Ukraine, automatically placed all citizens of Ukraine who shared the views of Crimeans into the category of state criminals. No legal public organization could declare such ideas. After the start of the war in Donbass, those who supported Donetsk and Lugansk were brutally dealt with in the rest of Ukraine - at best, they were arrested and tried, and at worst, they were subjected to physical destruction, as happened with the opponents of the Maidan on May 2, 2014 in the House trade unions in Odessa.

The only thing left for the Russians in Ukraine was resistance - first civil disobedience, and then armed struggle.

No comments:

Post a Comment